The Failure Of A Gold Refinery

So this happened: Republic Metals, a gold refiner, filed bankruptcy on November 2. The company had found a discrepancy in its inventory of around $90 million, while preparing its financial statements.

We are not going to point the Finger of Blame at Republic or its management, as we do not know if this was honest error or theft. If it was theft, then we would not expect it to be a simple matter of employees or management walking out the door with the gold. $90 million is about 2.6 tons. Unless it happened very slowly, over many years, that seems like a lot of gold to disappear. And if it occurred over years, why didn’t regular audits and other internal controls catch the discrepancy until now?

We want to make a different point altogether. We define inflation as the counterfeiting of credit. Legitimate credit has four criteria. Most of the focus is on the latter two: the borrower has both the means and intent to repay. Did Republic have the means to repay? They had a good business for 38 years, so we will assume yes. Did they have the intent? Well, unless this was a simple theft and theft by the owners, then we have to answer yes again (with one quibble which we will get to, in a moment).

The other two criteria are often overlooked. Does the lender know he is extending credit, and does the lender agree to do so?

This is a real problem in the regime of irredeemable currency. People think if they have a Federal Reserve Note (i.e. a dollar bill) that they have money. In fact, they do not. They have extended credit—lent—to the Federal Reserve. The Fed further lends it on to the US government or to the banking system. As an aside, this is a very aggressive kind of not-knowing. People seem to want not to know. Even after one explains it, they still don’t.

And even when people know that the Fed uses their credit to finance the government and banks, they have no way to express their disapproval. And they have no way to opt out. That is the (evil) genius of the design of our monetary system—it disenfranchises the saver.

Anyways, back to Republic. We will skip over the banks who are the secured lenders, they obviously knew they were lending. And will also not address the biggest unsecured creditors, such as a subsidiary of Tiffany & Co. They’re sophisticated and they knew (or should have known).

It is the small unsecured creditors, especially the mom-and-pop jewelers and pawn shops, who may not have thought about it. All they may have known, is that they send their gold to the refiner, and then either metal or cash shows up in their account.

If pressed, they might have thought (they know better now) that their metal was kept segregated until it was melted and then they got paid. And that may be true, but refining gold is not completed in a single instant in time. It takes a finite amount of time. And after it’s complete, the refiner policy may be to pay after a certain amount of additional time. Why would they do this? It’s called float, and they can use it as credit to finance their operations.

The key takeaway is that between the moment the gold is melted and the moment the cash is sent to your bank, you are a creditor. You have exposure to the refiner.

There is nothing intrinsically bad about being a creditor. However, it should come with obligations on the debtor including transparency. And interest! The borrower is getting value, and he should pay for it.

Now this brings us back to our quibble about intention to repay. Refiners can accumulate a large quantity of low-grade material such as gold-bearing sludge. This stuff can accumulate for years, because it takes a lot of it to get a little bit of gold and so long as the refiner has customers paying the ask price for refining services, it just may not be worthwhile to occupy the plant by processing this sludge.

Also, the amount of gold actually contained in this sludge may be inconsistent, varying with each batch added to the pile. And the amount recovered out of it could also be a bit unpredictable, as the refiner is normally set up for higher-grade material.

This is all fair enough, but then there are two corporate policy implications to this. One, this pile of low-grade material should be valued very conservatively. It’s basically found money (found gold). Two, you cannot finance this shit (yes, we use that word deliberately here)! That is, there should not be liabilities matched to it on the books. The company should be solvent, without including this material as an asset.

And you certainly should not use short-term funding, such as a credit line or even a term facility that has to be rolled every year or few years. Not if you don’t plan to liquidate the metal in the sludge during that time. Not only is the timing of liquidation (i.e. maturity) long-term and unknown, but the quality and hence value of this asset is also uncertain.

We have not written in a long while about the evils of duration mismatch. This is typically done by banks, but here is an example of the practice in a refiner. Funding a long-term asset with a short-term liability. If your credit line must be rolled every year, but your asset is not going to be liquidated (or amortized) for 10 years, you have a mismatch.

You run the risk that, if the credit cannot be rolled, you are forced to default. In this case, the owners (equity) lose everything. And the unsecured creditors could lose everything (as seems likely with Republic).

We would take this to its logical conclusion. If a debtor is engaged in duration mismatch, it is betraying its intent not to repay. At least for a long period, it intends to repay old creditors by borrowing from new creditors.

This is guaranteed to blow up sooner or later. And note that it has nothing to do with fractional reserves. Or in this case, even banking.

Due to the aforementioned feature of irredeemable paper currency—that the saver is disenfranchised and cannot express his preferences or opt out—borrowers may become very casual about their creditors’ money.

It won’t work in gold. Gold requires a different level of transparency, and with that also honesty in operations, finance, and accounting.

At least if it is to be the basis of a monetary system once again.

With gold, people can choose not to participate. They can take their gold home. As they do now. The official estimate of the amount of gold held in human hands is 187,000 tonnes, worth around $7 trillion (and we believe the actual amount is far higher). Proper gold credit is a tiny fraction of that, and even gold derivatives are a fraction of $7 trillion.

If gold is ever used as money again, the ratio of credit to gold metal will not be a fraction well under 1. It will be greater than 1:1.

This Report was written from Vienna. Keith is also visiting Madrid, Zurich, Hong Kong, Singapore, Sydney, and Auckland. If you would like to meet, please contact us.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

Yesterday was Veterans Day, a bank holiday in the US.

The prices of gold and silver dropped $23 and $0.61 respectively. “But isn’t gold supposed to go up when…?”

Why?

Because everyone else will bid it up.

Why?

Because they expect someone else to bid it up.

Why?

Warren Buffet is right (though quite disingenuous). Gold has no utility. People buy it, either expecting the end of the world, or price gains. And the latter is not happening right now, so even for those who buy it as a portfolio hedge are not feeling urgency.

Certainly not as much urgency as those who are liquidating.

Ultimately, people will buy gold to avoid being a creditor to the Fed. And on that day, price will not matter (and hence will be skyrocketing). But good ol’ Aragorn had it right “today is not that day.”

Now let’s look at the only true picture of the supply and demand fundamentals of gold and silver. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). It rose this week.

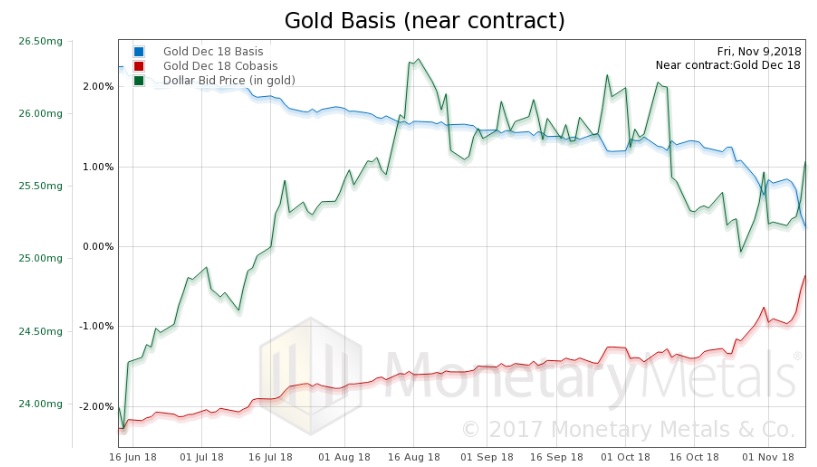

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

Look at that big rise in the paper currency that everyone loves to hate! It went up over 0.4mg gold!

Of course, most people see this move inverted—a drop in gold. With the drop in the price, gold became a bit scarcer (not so much for farther months—December is nearing expiry and hence is under selling pressure).

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price dropped $26, $1,314. This is a rare time when the fundamental moved essentially with the market price. For whatever, the price was driven this week by the selling of physical gold metal.

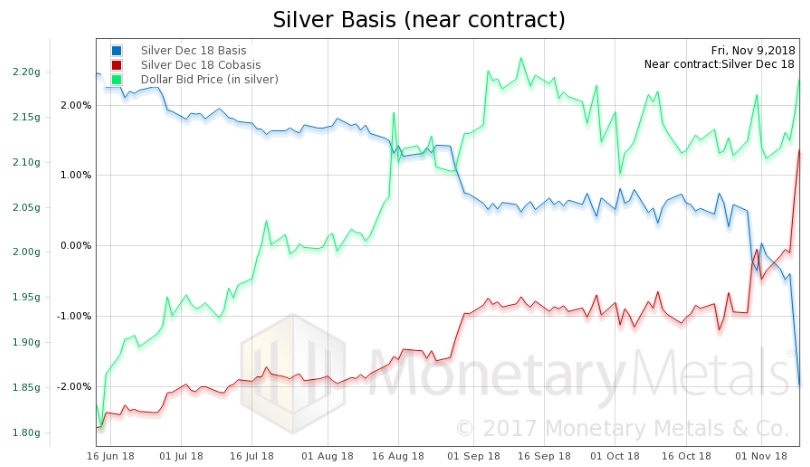

Now let’s look at silver.

Silver shows a sharper rise in scarcity (i.e. the cobasis).

The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price fell 34 cents, to $15.22.

© 2018 Monetary Metals

Dr. Keith Weiner is the CEO of Monetary Metals and the president of the

Dr. Keith Weiner is the CEO of Monetary Metals and the president of the