Central Planning Is More than Just Friction

It is easy to think of government interference into the economy like a kind of friction. If producers and traders were fully free, then they could improve our quality of life—with new technologies, better products, and lower prices—at a rate of X. But the more that the government does, the more it burdens them. So instead of X rate of progress, we get the same end result but 10% slower or 20% slower.

Some would go so far as to say, “The free market finds ways to work even through government restrictions, taxes, and regulations.” We won’t address cardboard straws emerging where plastic straws are banned. Or gangs selling illegal drugs on the black market, when they are prohibited by law.

As usual, we want to talk about the most important kind of government intervention. And it happens to be the one kind of government intervention that is accepted by nearly everyone. The intervention supported by the otherwise-free-marketers.

Monetary intervention.

Under monetary central planning, do people work at the same tasks, at the same companies they would have worked in a free market, producing the same goods? And is the only consequence, that goods have a higher price (due to inflation)?

Can we treat the dollar as a universal constant, if we adjust it for the change in prices?

Keynes and Lenin

We will trot out that infamous quote of Keynes citing Lenin, again. From Consequences of the Peace:

“Lenin is said to have declared that the best way to destroy the Capitalist System was to debauch the currency. By a continuing process of inflation, governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. The sight of this arbitrary rearrangement of riches strikes not only at security, but at confidence in the equity of the existing distribution of wealth. Those to whom the system brings windfalls, beyond their deserts and even beyond their expectations or desires, become "profiteers," who are the object of the hatred of the bourgeoisie, whom the inflationism has impoverished, not less than of the proletariat. As the inflation proceeds and the real value of the currency fluctuates wildly from month to month, all permanent relations between debtors and creditors, which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism, become so utterly disordered as to be almost meaningless; and the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery.”

The first part would fit with the above-stated premise. Government confiscates, and make the people poorer. The same as they had been, only a bit less in proportional to the amount confiscated. However, the next part observes that the confiscation harms most people but enriches a few, arbitrarily.

Think about a serious inflation. Suppose prices are going up 10% a year. Some businesses will have the foresight to buy extra raw materials. This hoarding enables them to make extra profits when they sell their finished goods, months or a year later. They could make even more, if they borrowed to finance even-greater hoarding. This is a picture of the 1970’s.

Now let’s look at the next part of that quote. It breeds resentment. Are we there yet, today? Nearly everyone takes so-called inequality to be a problem, with the Left moving on to the solution phase (taxes, of course).

We will skip to the last part for a moment. “…Wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble…” Buy stocks, buy real estate, buy bitcoin, and even buy gold. Everyone just wants to know what asset will go up next. Few question if this central-banking assets-going-up mechanism is destructive.

Now back to the most interesting part of the quote. This theme is not often written-about. The relationship between debtor and creditor is the foundation of capitalism. Keep in mind, this is coming from Keynes, about whom Benito Mussolini, the fascist dictator of Italy, said:

“Fascism entirely agrees with Mr. Maynard Keynes, despite the latter’s prominent position as a Liberal. In fact, Mr. Keynes’ excellent little book, The End of Laissez-Faire might, so far as it goes, serve as a useful introduction to fascist economics. There is scarcely anything to object to in it and there is much to applaud.”

And Keynes is claiming that the origin of the above quote about destroying capitalism, is actually the communist butcher, Vladimir Lenin. Neither of these two were for capitalism, free markets, or freedom. And yet they think that the credit relationship is the foundation of capitalism.

As an aside, this touches on the age-old question of what is money. Is the dollar money? Or is gold money? Or are they both money, and gold just better money? There is no question that the dollar is the generally-accepted medium of exchange. But is medium of exchange the definition of money?

If one thinks of capitalism as merely people buying and selling in a market, then why isn’t this definition right? What else could money mean, other than medium of exchange?

But, if one thinks that the creditor-debtor relationship is vitally important (much less the foundation of capitalism), then one has a reason to question this definition. Money must perform the function of extinguishing debt.

The dollar cannot perform this function.

And indeed, Keynes and Lenin understood that the government can destroy the capitalist system by debauching the currency. Note that, twice they use the word “currency”, but not the word “money”. Keynes understood something in 1920 that many people do not, today.

Why would the credit relationship be the foundation of capitalism? Can’t people buy and sell things without credit? Consumers can certainly buy consumer goods without credit.

But what about producers?

The Foundation of Capitalism

Production, even in an industrial economy of the form that existed before World War I, occurs at large scale in factories full of machines. The enterprises who own and operate these factories depend on credit to finance them. Without credit, such factories would not exist and civilization would be dragged backwards to a much less efficient mode of production. Goods we take for granted would not be available at all. Basic necessities like food and clothing would be far more expensive. And wages would drop drastically, with the drop in productivity.

Of course, earning interest is important to people who work for wages, and also to retirees who live on the income on their savings. If the government destroys the relationship between creditor and debtor, then workers are impeded in saving for retirement. And retirees must consume their meager savings.

Suppose it is true, that industrial production and distribution is capital-intensive. Suppose it is true that this capital is provided by creditors. Suppose it is true that workers and retirees need interest…

Maybe Lenin and Keynes were right (in this one premise), that the relationship between creditor and debtor is sacred, and the foundation of the modern economy.

One thing is for sure. The price of borrowing money (i.e. interest rate) affects the price of everything else. And if the rate goes too high, producers begin to be bankrupted. Just as if the rate falls to low, producers are destroyed (by a different means).

Let’s tie this back in to the topic we opened at the start of this essay. Government interference in the credit market does not merely slow the economy. It stops some people from engaging in wealth-creating production and trade. And encourages other people to engage in wealth-consuming activities instead. That is, the altered price of credit alters, in turn, the incentives that drive everyone in the economy.

When people blame the so-called one percent, when they rail against so-called late-stage capitalism, when they decry inequality, they are the leading edge of what was described by Lenin:

“Those to whom the system brings windfalls… become "profiteers," who are the object of the hatred of the bourgeoisie, whom the inflationism has impoverished, not less than of the proletariat.”

This is our motivation to re-develop a market for interest on gold, not subject to the central planners.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

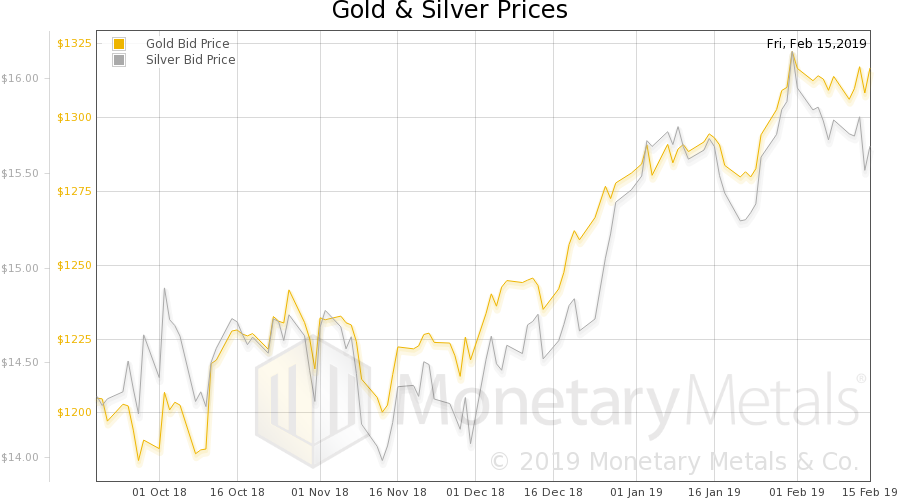

Yesterday was Presidents Day in the US. The price of gold rose last week a bit, but silver not so much.

To understand if stocks will crash, don’t look at indicators which may be lagging or at best coincident. Jobs data or GDP won’t tell you what’s going to happen to stocks. Even earnings (which, in theory, is based in part on GDP) can’t tell you much.

It’s credit.

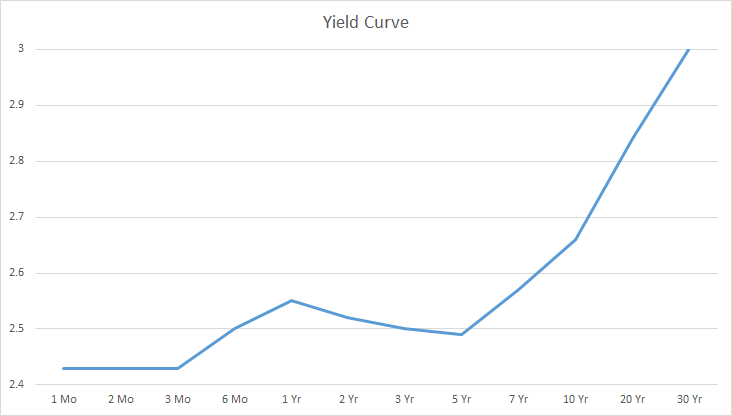

Today, we thought we would talk about yield curve. Here is a graph showing all maturities from 1-monthy to 30-years.

We have done something with this graph that one normally shouldn’t do (and you should always be on the lookout for). We have started the vertical axis, not at 0 but at 2.4. We did this to zoom in on the curve, which is very flat. Note that 1-month is 2.43% and 5-year is 2.49%. That is 6 basis points difference between lending for a month vs five years. Yikes!

We say “yikes” because banks engage in what is euphemistically called “maturity transformation”. That is, they borrow short to lend long. This is an unstable practice. Without getting into the theory here, let’s just say that if the yield curve is flat then banks cannot make money. If it inverts, they are losing money.

The Fed has driven the market to this state, because of course it has control of the overnight rate. So the shorter maturity Treasurys such as 1-month move nearly in lockstep with the Fed. However, demand for credit is soft. So the rate on bonds is not very much above the Federal Funds Rate (currently 2.4%).

The Fed is being hawkish, while the credit market is being tepid.

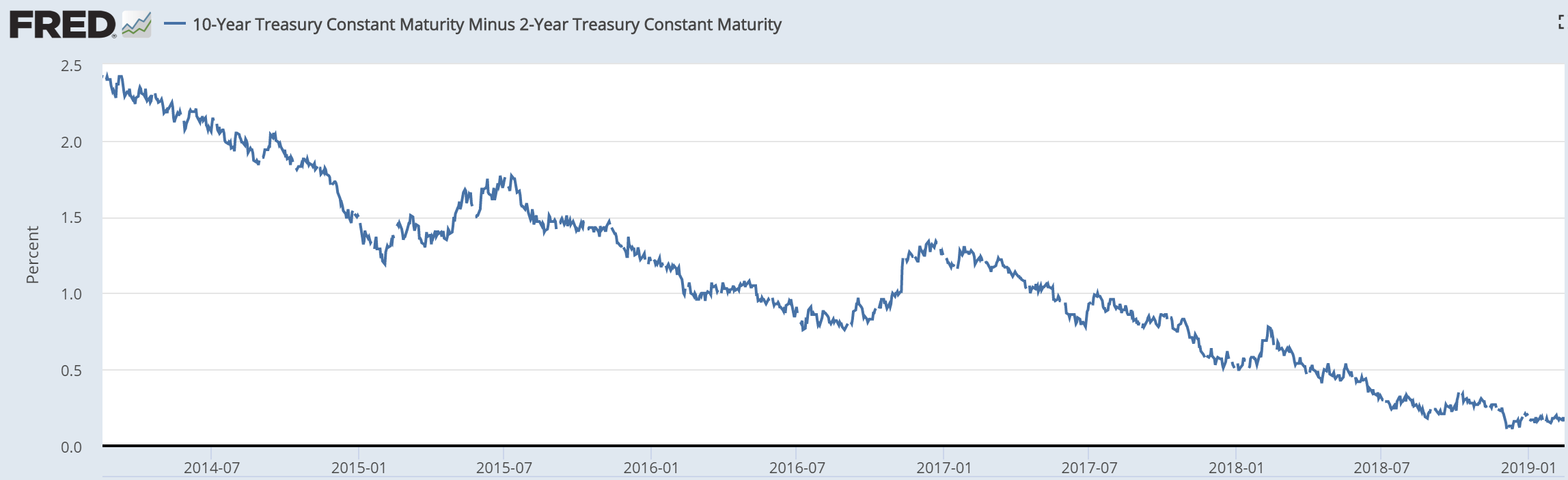

Here is a chart showing the spread between the 2-year and 10-year bond, for five years.

It’s been falling for a long time.

Think of this in terms of the decades-long trend of rising asset prices, which is the same as saying the trend of falling yields. Now, the Fed thinks to push down bond prices. But it does not have control over the long bond price, only the Fed Funds Rate. Meanwhile, the bond price wants to go up, while the price of the short-term bill is forced down. There will be inversion, if the Fed persists.

What will give? Will demand for credit suddenly spike? Color us skeptical. Will the Fed back down, and begin cutting rates? Or will defaults begin to cascade? We think the latter is the most likely.

Now let’s look at the only true picture of the supply and demand fundamentals of gold and silver. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). It was up this week.

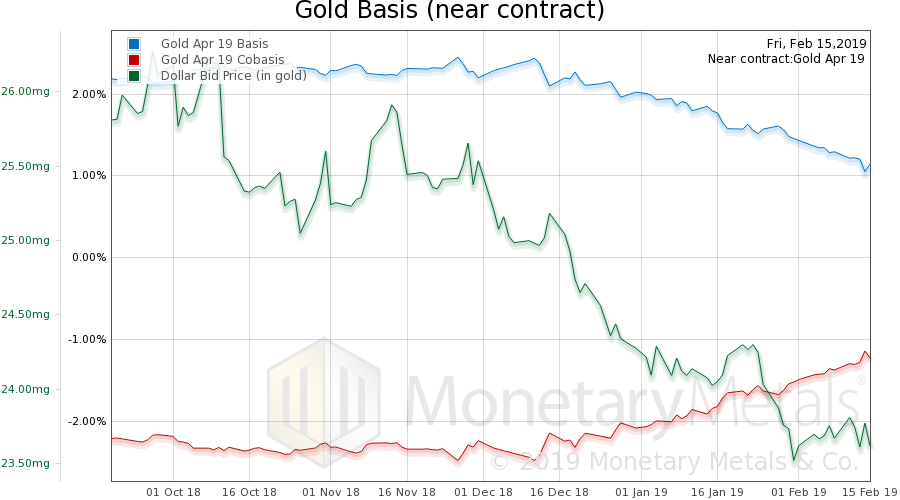

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

Gold is scarcer, and its price is up. For years (with many gold writers promising gold to skyrocket any-day-now all the while), we did not see this pattern. A higher gold price meant higher basis (blue line) and hence abundance. A higher gold price was due to speculators buying futures.

Now, we see the opposite. A higher gold price is due to buying of metal. Will this new trend endure? Stay tuned!

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price has broken above $1,400 for the first time since Q2 last year (and before that, 2016), now $1,407.

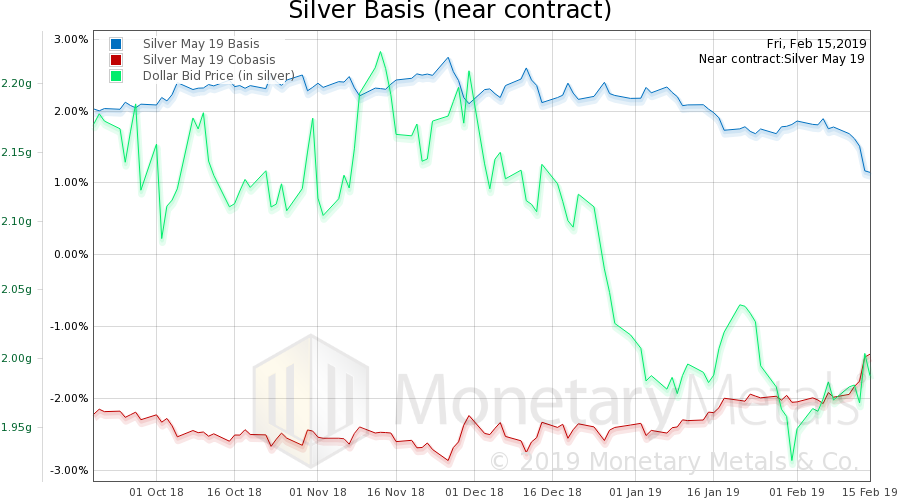

Now let’s look at silver.

The silver cobasis (i.e. scarcity) shows an even bigger move this week. This is the May contract, so should not be under selling pressure due to the contract roll yet—it is under buying pressure from the roll of the March contract.

The price of silver may have dropped a bit this week, This is another long trope of the gold and silver writers, but this week in silver it is true: futures sold a bit but physical is being bought.

The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price rose 43 cents to $16.52

© 2019 Monetary Metals

********

Dr. Keith Weiner is the CEO of Monetary Metals and the president of the

Dr. Keith Weiner is the CEO of Monetary Metals and the president of the