Will the Fed Cause an Inflation Mountain by Lowering Rates Too Soon

US producer prices increased by the most in three years in July amid a surge in the costs of goods and services, suggesting a broad pickup in inflation was imminent, Reuters reported in mid-August.

“This is a kick in the teeth for anyone who thought that tariffs would not impact domestic prices in the United States economy,” Reuters quoted Carl Weinberg, chief economist at High Frequency Economics.

Bloomberg agreed that companies are starting to pass on higher input costs to their customers after months of “eating them”. The higher costs are weighing on corporate earnings, putting shareholder pressure on firms to maintain profit margins and “pass through” the tariffs.

The Producer Price Index (PPI) in July rose 0.9% from June, the largest advance since consumer inflation peaked in June 2022, said a report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). It climbed 3.3% from a year ago.

“New tariffs are continuing to generate cost pressures in the supply chain, which consumers will shoulder soon,” Samuel Tombs, chief US economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, wrote after the BLS report, via BBC News.

“While businesses have assumed the majority of tariff costs increases so far, margins are being increasingly squeezed by higher costs for imported goods,” Ben Ayers, senior economist at Nationwide, said in a note. “We expect a stronger pass through of levies into consumers prices in coming months with inflation likely to climb modestly over the second half of 2025.”

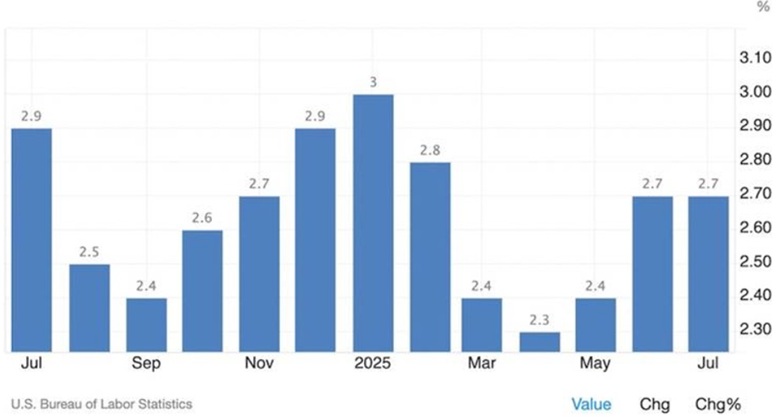

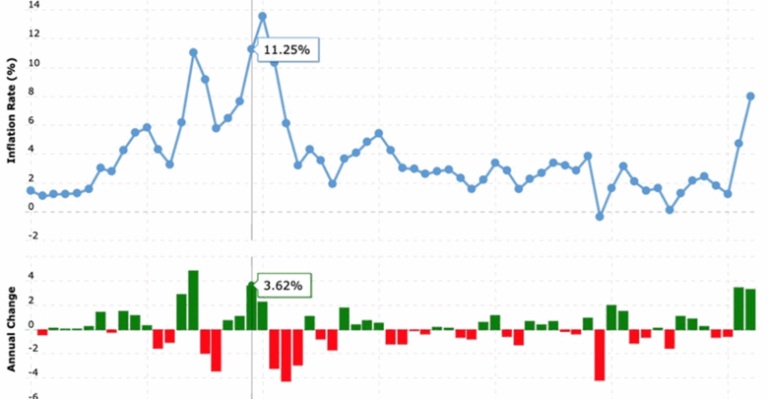

US inflation. Source: Trading Economics

The Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index was +2.6% in July, and the core PCE (goods and services minus food and fuel, and the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation) was +2.9%, up from 2.8% in June and the highest since February.

The broader CPI was flatter than expected at +2.7%.

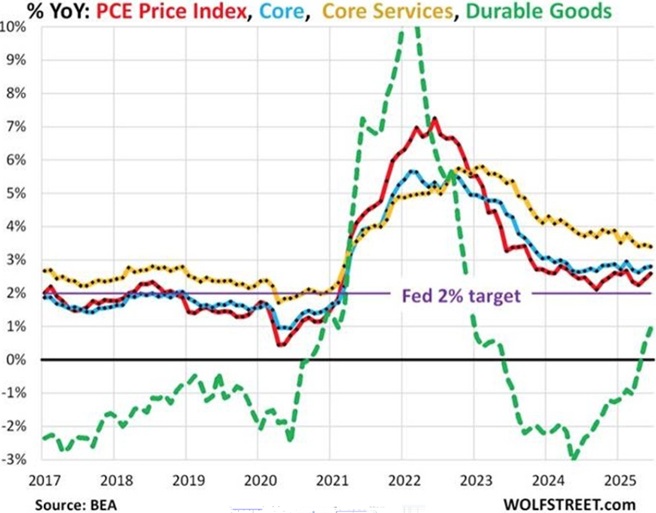

Wolf Street notes The core services PCE index, at +3.4% (yellow) for the third month in a row, is substantially hotter than in the pre-pandemic years and the biggie that keeps core PCE and overall PCE well above the Fed’s [2%] target.

Inflation Rate Source: Wolf Street

If inflation is rearing its ugly head again, after the Fed cut it off through a series of interest rate hikes between 2021 and 2023, why is there talk of lowering interest rates when the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meets next on Sept. 16-17?

Isn’t it against the laws of basic economics for the central bank to be slashing interest rates, which heats up the economy and adds to inflation, when inflation is already on the rise without any rate cuts?

The reason, as we shall see, has more to do with power and politics than sound economic policy.

The return of inflation and the goosing retail investors: Got gold? — Richard Mills

Inflation mountains

History is prologue, a wise man once said.

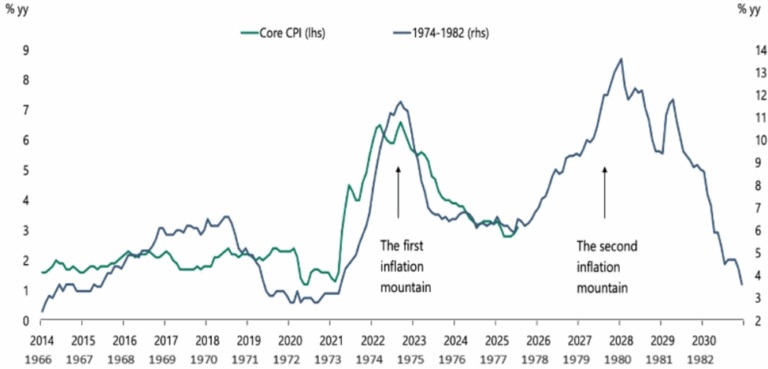

Economist Torsten Slok produced an interesting chart showing how the inflation cycle of today resembles that of the 1970s.

Slok, a Danish-American, is no slouch. Formerly with Deutsche Bank and now with Apollo Global Management, his charts are well-read around Wall Street. His market analysis earned him a profile in Bloomberg, and he was one of the first prominent voices to warn of a potential AI bubble in stocks this summer — warning how shares of Nvidia, Microsoft and eight other companies are creating an even bigger bubble than the one during the dot-com era.

Now Slok is warning of an “inflation mountain” in a potential repeat of the 1970s and ‘80s.

In the chart below, the core CPI (the price increase of goods and services minus food and fuel) is tracked over the period 1966 to 1982, on the X axis, and between 2014 and 2030. The Y axis on either side is the percentage increase in inflation, year on year.

Source: Apollo Global Management

Zooming out on the chart, we see “foothills” that are a near mirror image of each other from 1966 and 1973, and from 2014 to 2021. The rate of inflation never rises about 3.5% in either time period.

Now to the mountains. The first inflation mountain forms between 1973 and 1975, levels off for a couple of years, then a second mountain rises up between 1978 and 1982. Inflation reached a high point during this period of 14% in 1980.

It’s important to understand the difference between the green line, which represents inflation between 2014 and 2025, and the black line, which is 1970s and 1980s inflation.

What were the “policy missteps” that caused the second inflation mountain to form in the late 1970s, early ‘80s?

In the 1970s, the Fed cut interest rates too soon after an initial inflation spike, only to see prices surge again as oil shocks and wage demands rippled through the economy. That forced policymakers to slam rates back up, tipping the U.S. into repeated recessions and damaging the Fed’s credibility for years.

For Slok’s theory to be correct, inflation over the next five years would have to rise up and form a second mountain similar to the one between 1978 and 1982. More specifically, if the pattern holds, inflation would be due to scale another peak starting in the fall of 2025, i.e., now.

Also, for Slok to be right, the Fed would have to cut interest rates, as early as this month. This, in his view, is the policy mis-step that leads to the second mountain of rising inflation.

In his ‘Daily Sparks’ newsletter of Aug. 31, Slok noted inflation expectations from tariffs, dollar depreciation, and disagreement within the FOMC about how to balance rising inflation with slowing employment (the Fed has rarely cut rates against a backdrop of rising inflation).

The Fed is arguably bumbling into a similar policy mistake that they made in the 1970s, that of cutting rates too soon after an initial inflation spike — the one we described at the top of the article with the July inflation print.

Slok warned about this at the Jackson Hole Symposium in August, where he said the Fed see structural distortions from tariffs and immigration policy.

(Tariffs are inflationary because they force importers to pay an extra “tax” on imports, that are eventually passed onto consumers. Immigration restrictions are inflationary because they pull workers out of the economy. The removal of workers is pushing up wages in industries like agriculture, construction and hospitality.)

If those forces keep inflation sticky and Powell cuts rates, as he’s under pressure from the White House to do, Slok wrote that he could be vulnerable to a 1970s-style “stop-go” policy mistake — the backdrop for the second inflation mountain.

In such a scenario, reminiscent of the ‘70s, if the Fed loosens policy prematurely, inflation could spike, leading to the painful corrective measures seen under Powell’s predecessor Paul Volcker, who hiked rates aggressively and weathered severe, double-dip recessions. — Fortune

Before we leave this section, a bit more about the economic condition of the 1970s and 80s.

When inflation was hitting 40-year highs in 2022 many, including us, were compelled to look back in history at when this last happened.

1979 vs 2022: Why interest rate hikes are different

In 1979, then US Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker faced a serious challenge: how to quell inflation which had been wracking the economy for most of the decade. The prices of goods and services had averaged 3.2% annually since World War II, but after the 1973 oil shock, they more than doubled, to an annual 7.7%. Inflation reached 9.1% in 1975, the highest since 1947. Although prices declined the following year, by 1979 inflation had reached a startling 11.3% (led by the 1979 energy crisis) and in 1980 it soared to 13.5%.

Not only was inflation going through the roof, but economic growth had stalled, and unemployment was high, rising from 5.1% in January 1974 to 9% in May 1975. In this low-growth, hyperinflationary environment we had “stagflation”.

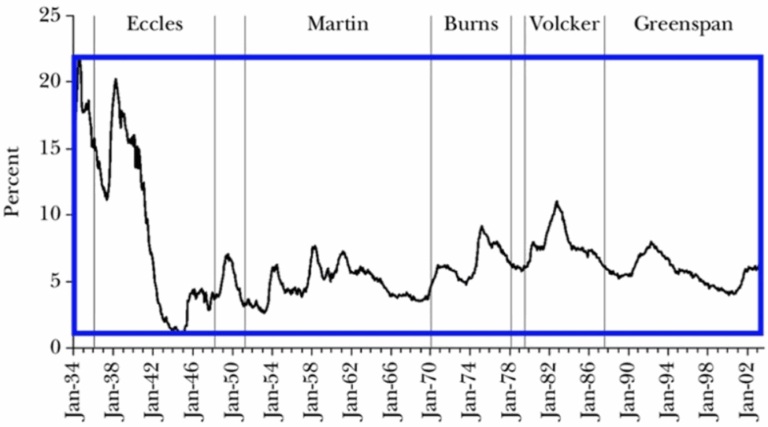

Volcker is widely credited with curbing inflation, but in doing so, he is also criticized for causing the 1980-82 recession. He did it using the same playbook as the current Federal Reserve: by raising the federal funds rate. Except he was way more aggressive. From an average 11.2% in 1979, Volcker and his board of governors through a series of rate hikes increased the FFR to 20% in June 1981. This led to a rise in the prime rate to 21.5%, which was the tipping point for the recession to follow.

But we need to back up. Volcker is blamed for causing the 1982 recession, but it was the previous Fed Chair William Miller that forced his hand. Miller, who was Chair between 1977 and 1979, is considered to have gone too easy on inflation by refusing to raise interest rates to quell demand. He left the dirty work to Volcker.

According to Federal Reserve history,

As chairman at the Board of Governors, Miller became known for his expansionary monetary policies. Unlike some of his predecessors, Miller was less focused on combating inflation, but rather was intent on promoting economic growth even if it resulted in inflation. Miller argued that the Federal Reserve should take measures to encourage investment instead of fight rising prices. He believed that inflation was caused by many factors beyond the Board’s control.

In a 2004 paper published in the ‘Journal of Economic Perspectives’, titled “Choosing the Federal Reserve Chair: Lessons from History”, authors Christina and David Romer state that:

The effects of Miller’s relatively expansionary policy (as well as the lagged effects of Burns’s last hurrah) are obvious in Figures 1 and 2. The unemployment rate fell steadily in 1978 and early 1979, and inflation surged even before the oil price shock in the second half of 1979.

Source: Global Financial Data. The small gap between Burns and Volcker is the Miller era.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Great Inflation

The 1970s has become known as a decade of failed monetary policy. The Great Inflation lasted from 1965 to 1982.

When President Nixon was inaugurated in 1969, he inherited a recession from President Johnson, who had spent generously on the Vietnam War and the Great Society, a series of social programs aimed at reducing poverty.

Nixon famously entered office as a fiscal conservative and left it as a free-spending Keynesian. In 1972, for example, Congress and Nixon agreed to a big expansion of Social Security, in time for him to get re-elected the same year.

According to Investopedia, The Great Inflation was blamed on oil prices, currency speculators, greedy businessmen, and avaricious union leaders. However, it is clear that monetary policies that financed massive budget deficits and were supported by political leaders were the cause.

Nixon’s other economic about-face was imposing wage and price controls in 1971. As inflation began creeping higher, Nixon temporarily froze prices. When his controls were lifted, prices bounced even higher, into double digits.

In 1971, Nixon severed the US dollar’s link to gold, turning the dollar into a fiat currency. Investopedia notes, the dollar was devalued, and millions of foreigners holding dollars, including oil barons in the Middle East with tens of millions of petrodollars, saw their value slashed.

In 1972 and ’73, Fed Chair Arthur Burns started to worry about inflation, which by 1973 had more than doubled to 8.8%. By the end of the ‘70s it was 12% and by 1980 it was at 14%.

It was the actions of Fed Chair Paul Volcker that would finally tame inflation through a series of brutal interest rate hikes.

NPR notes that by 1983, inflation had retreated to just over 3%, but at the cost of about 4 million job losses during back-to-back recessions in the early 1980s. For the next four decades, inflation wouldn’t become a problem until the pandemic struck in 2020 followed by the war in Ukraine. In June 2022 inflation reached 9% for the first time in 40 years.

Ten Year US Treasury Yields Source: Macrotrends

Is a Volcker-like series of rate hikes in the cards? — Richard Mills

Fed pivots to unemployment

In early June the Labor Department reported that the federal government has shed 59,000 jobs since January.

Just 73,000 jobs were added in July, with the monthly totals for May and June revised down by a combined 258,000 jobs (CNN).

“It’s stalling out right now,” Diane Swonk, chief economist at KPMG, said of the labor market.

With those monumental, quarter-million-job downward revisions, the meager job gains in June were the weakest since December 2020, the last time the labor market had monthly job losses. The pace of job creation seen so far this year is the weakest in decades, outside of recessions.

“This is absolutely the worst major economic report since the end of the pandemic era,” Joe Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM US, told CNN.

The Labor Department said the hiring rate was just 3.3% in June, which is well below the pre-covid average of about 3.9% and in line with levels generally associated with recessions.

The latest jobs report provides more reasons for pessimism.

On Friday(Sept 5th) Bloomberg reported that Disappointing employment data validated fears that the US labor market may be on the brink of a downturn and lifted expectations for how much the Federal Reserve will lower interest rates this year.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employers added 22,000 jobs in August and the unemployment rate rose to 4.3%. Job cuts went up 88,736 in August — the highest August total since 2020.

Bloomberg continues:

The figures — including revisions that showed payrolls were negative in June for the first time since December 2020 — locked down expectations that officials will need to intervene this month to support the labor market, even as inflation remains above the Fed’s 2% target and may head higher because of tariffs…

Even prior to the latest jobs report, a substantial slowdown in payroll growth over the summer had prompted comments from Fed Chair Jerome Powell and other policymakers that the balance of risks was shifting away from inflation and toward unemployment.

A Sept. 5 Reuters story is titled ‘US labor market cracks widen as job growth nearly stalls in August’. It says “Job growth has shifted into stall-speed, with economists blaming President Donald Trump’s sweeping import tariffs and an immigration crackdown that has reduced the labor pool. Softness in the labor market is mostly coming from the hiring side. There were more unemployed people than vacancies in July for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Digging deeper into the unemployment numbers the July Jolts report showed U.S. job openings fell to the lowest in 10 months, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported. Available positions decreased to 7.18 million from a downwardly revised 7.36 million in June.

Neil Dutta, head of economic research at Renaissance Macro Research, said in a note that the decline centered on state and local government job openings. “This is notable because these acylical parts of the jobs market have been the areas lifting employment growth the most,’’ Dutta said. “If you lose these acyclical areas you don’t really have much else [to] keep payroll growth with a plus sign in front of it.”

Investors are now pricing in a 0.25% rate reduction at the Fed’s meeting on Sept. 16-17.

Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller on Wednesday repeated his call for an interest-rate cut in September given the weakening labor market. Over the next three to six months, they could see multiple cuts coming, Waller, who is a potential successor to Powell, said in an interview with CNBC.

Inflation causes and effects

Beyond tariffs and immigration restrictions, there are other reasons why inflation is becoming a problem: one is the lower dollar, and the second is what happens if foreign buyers fail to purchase US Treasuries in the numbers the US has been accustomed to. A drop-off in overseas Treasury buying would force the Fed to buy them at auction. How does it find the money to do this? It prints it, which is inflationary.

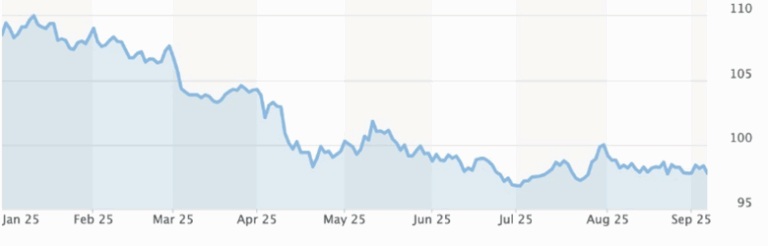

Since Donald Trump took office in January 2025, the US dollar index (DXY) has fallen by 11.8%. A weak dollar generally means worse tariff inflation. That’s because; If the global demand for the greenback is down — and most global trade is transacted in dollars — that limits the likelihood that foreign companies will reduce prices for U.S. importers looking to offset the cost of Trump’s tariffs. (Politico)

Source: MarketWatch

Why has the dollar fallen? It mainly has to do with Trump’s economic policies.

Is the US dollar done? — Richard Mills

Donald Trump has boldly imposed a new era of US economic policy dominated by tariffs, trade wars, and threats to the sovereignty of nations it has long considered allies (Canada, Denmark, Panama), as the second-term president aims to rewrite the rules of international trade mostly by disregarding them as he pursues an America-first agenda.

The cost to the United States of Trump’s trade war and “country takeover” rhetoric has already cost America its reputation.

“De-dollarization” is being pursued by countries with agendas at odds with the US, including Russia, China, Iran and now, very likely India.

As the target of US economic sanctions (for annexing Crimea, interfering in its election, and invading Ukraine), Russia sees diversification from the dollar and into gold and other currencies as a way of skirting sanctions.

After Russia’s full-scale Ukraine invasion, the US and its allies froze Russian foreign exchange reserves in their jurisdictions. By late July 2023, the amount of frozen Russian assets held in these countries was estimated at $335 billion.

Many countries including the BRICS saw what happened to Russia and have been purchasing gold bullion to store in their central bank vaults instead of dollars, lest they get on the wrong side of Washington.

Russia and China have both made moves to de-dollarize and set up new platforms for banking transactions outside of SWIFT.

Most Russia-China trade is now conducted in Chinese yuan or Russian rubles, with the US dollar almost completely bypassed.

Before Trump’s electoral victory last November, Japanese investors sold a record $61.9 billion US Treasuries in the three months ended Sept. 30, data from the US Department of the Treasury showed. Funds in China offloaded $51.3 billion during the same period, the second biggest sum on record. (BNN Bloomberg)

China reportedly reduced its official holdings of US Treasuries by more than 27% from January to December 2024 — much faster than the 17% it dropped in seven years from 2015 to 2022 (The Financial Times).

In mid-April, when Trump announced so-called “reciprocal tariffs” on dozens of countries including a monstrous 145% tariff on China, another round of Treasury selling ensued.

This was evidenced by the yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury soaring to nearly 5%, the highest since February, and the 30-year bond notching its highest level since November 2023. Bond sales like these knock bond prices down and cause yields to rise.

The phenomenon was unusual, since Treasuries are considered a safe haven and foreign investors normally flock to them (and gold) during periods of economic turmoil.

One Year Gold Chart Source Trading Economics

US government bonds are no longer seen as the go-to safe-haven asset.

Since Trump has returned for a second term, his tariffs and trade war has accelerated the decline of the dominance of the dollar, not slowed it. (Geopolitical Economy)

The latest foreign Treasury buyer to limit purchases is India. The country is reportedly leaning on gold to strengthen its foreign exchange reserves, while trimming its exposure to T-bills, which dropped to $227 billion in June 2025 compared to $242B a year earlier.

GE says it’s not only governments that are seeking alternatives to the US dollar but also major financial institutions and investors.

The Financial Times of Britain published an analysis from the global head of FX research at Deutsche Bank, who warned, “We are witnessing a simultaneous collapse in the price of all US assets including equities, the dollar versus alternative reserve FX and the bond market. We are entering unchartered territory in the global financial system.”

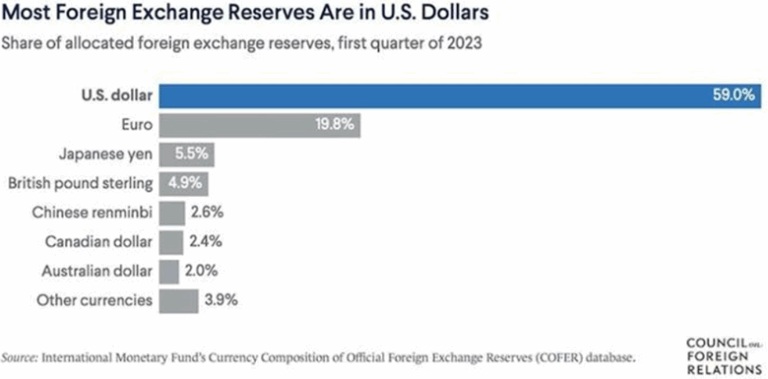

The US dollar’s share of foreign-exchange reserves has decreased, mostly in emerging markets.

According to IMF data, at the end of 2024, the dollar accounted for 58% of global foreign exchange reserves, while 10 years earlier that share was 65%.

Source: Council on Foreign Relations

Equally, the share of the US Treasury market owned by foreigners has also fallen sharply, from 50% in 2014 to around a third today.

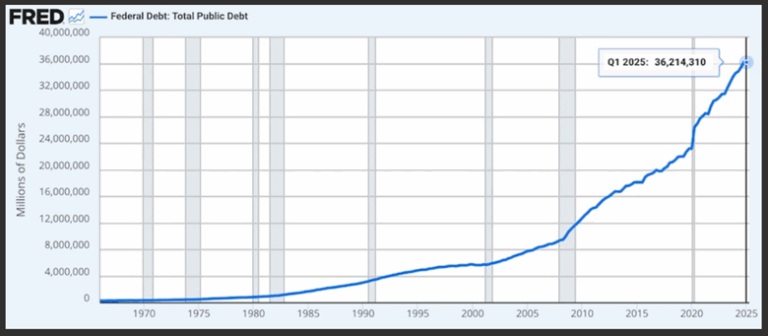

At $36 trillion and counting, interest payments on the national debt now surpass the entire US defense budget. Many countries are questioning the fiscal strength of the US economy and whether holding Treasuries is worth hitching their wagon to an economy that is so deep in the red.

Source: FRED

A recent article in Project Syndicate argues that rate cuts implemented by the Fed, encouraged by the Trump administration, could actually have the opposite intended effect on long-term interest rates.

That’s because the Fed only really controls shorter-term Treasury yields, like the 2-year note. But market forces determine rates on 10-year and longer-dated bonds. A key question is what do investors think is a fair rate, given the longer-term risks to the economy?

If the FOMC is effectively forced by political pressure (of any kind) to lower interest rates below what its members believe is consistent with that target, there might be more economic growth in the short run, but there will likely also be more inflation…

Political pressure can lower short-term interest rates, but, given the likelihood of higher inflation, long-term rates are likely to rise. For example, firing the chair of the Fed or any combination of governors, or taking any other extraordinary political measures is likely to raise long-term interest rates and make it more expensive to buy homes.

Concerns about the fiscal health of major economies from Japan to Britain and the United States kept long-dated borrowing costs pinned near multi-year highs. (Reuters) Japan’s 30-year bond yield pushed to a record high well above 3% this week.

The Globe and Mail reported in its Friday edition that concerns over inflation, US fiscal health, Federal Reserve independence and geopolitical instability are questioning the stability of long-term Treasuries, historically seen as the safest asset. A Reuters dispatch to The Globe says that as a result, many central banks are returning to gold. (Stockwatch)

Wall Street commodities investment firm Goehring & Rozencwajg is on side with the “inflationistas,” writing in a recent commentary that, One way or another, monetary policy will loosen. We are confident that Trump’s new appointee will arrive in his office; sleeves rolled up and rate cuts ready…

We are firmly in the camp that believes the great disinflationary arc, which began in the stern days of Paul Volcker’s Fed, has run its course. The era of falling yields and fading price pressures is over. In its place, a new cycle has begun—an inflationary one, with the potential to stretch across decades.

Source: Goehring & Rozencwajg

Influential investor and financial commentator Ray Dalio recently warned that the US dollar and other reserve currencies are waning in appeal due to high government debt burdens. The US government’s debt-service payments now equal about a trillion dollars a year in interest, with about $9 trillion needed to refinance the debt which will mature this year.

Dalio also warned the president’s efforts to shape monetary policy — by firing Powell before his term is up, packing the Federal Reserve’s board of governors with appointees who agree with his low-interest-rate monetary policy, and the contested firing of Governor Lisa Cook — could backfire.

“If the independence of the Fed is reduced to the point where investors think there is a high risk that interest rates being unnaturally lowered so that bonds won’t be a good store hold of wealth, we will see an unhealthy decline in the value of money,” Dalio wrote.

A top economist says the US is at the ‘Edge of the cliff’ and in a full-blown labor recession that risks spilling into the rest of the economy.

Moody’s economist Mark Zandi has been closely watching what he describes as a “labor recession” unfold, with revisions for June showing a contracting workforce for the first time since 2020. Friday’s report did nothing to dissuade him of the notion, and now the Moody’s economist told Business Insider he’s looking ahead for signs that the job-market downturn could spill into the broader economy.

Zandi sees a potential bump in the road coming on September 9, when preliminary benchmark revisions come in for earlier in 2025. The markdown in job additions is expected to be significant. Zandi also noted that these downward revisions and outright job losses are coming without a significant increase in layoffs. If companies were to accelerate on that front, Zandi says it would worsen the labor recession and possibly impact overall economic strength. “If businesses start laying [people] off, then I think this will not just be a jobs recession, will be an overall economic downturn,” he told BI.

Donald Trump and his administration are now saying it could be a year before the U.S. sees rosier economic data. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick agrees and said he expects the data to improve as more people are fired from the BLS.

Why strongmen love low rates

Trump has made it clear he wants Powell gone and for interest rates to be lowered after several meetings of keeping them on hold. The main reason Trump wants cheaper borrowing costs is so he can continue to run huge deficits and pay less in interest to service the debt.

The federal funds rate currently sits at 4.25 to 4.5%. The last time the Fed cut rates was on Dec. 18, 2024, when it reduced them by 0.25%.

It turns out Trump isn’t the only country leader who favors this policy.

A recent article in Project Syndicate answers the question, ‘Why Do Populist Strongmen Love Low Interest Rates?’

It’s a question worth asking because the policy often doesn’t work. It gives the example of Turkish President Erdogan, who forced Turkey’s central bank to cut rates even as inflation was climbing. The results were catastrophic; in 2022, Turkey’s inflation surpassed 80%, the currency plummeted, and household savings evaporated.

Argentina, India, Venezuela and Brazil have also demanded their central banks reduce interest rates.

The article backs up what was written in the last section, that it’s the market, not the short-term policy rate, that determines the long-term borrowing costs for governments, companies and households.

If a bank trusts its client’s finances and ability to repay, it will offer better terms.

Similarly, if investors trust a government’s fiscal trajectory, its institutions, and its monetary authority, they will be willing to let it borrow cheaply. If not, they will demand higher interest rates to compensate for the risk.

If fiscal credibility erodes or inflation expectations rise, market rates can move higher even as the Fed cuts the federal funds rate. This is what strongmen fail – or refuse – to grasp, and it explains why there has never been a growth miracle in a country with a populist government.

But the real reason that strongmen push for lower interest rates has nothing to do with economics; they do it because they need to get re-elected. Trump must have the support of both Houses of Congress to pass his MAGA agenda. If he loses the Senate, the House, or both, in the upcoming mid-terms, all bets are off.

What about tariffs? Project Syndicate says low interest rates come to the rescue by offering a temporary reprieve from the bad effects of tariffs:

If consumers and firms can borrow easily, they can “get by” without realizing that their incomes will be lower in the future.

The tariff-loving strongman must act quickly. If tariffs lead to slow growth and higher prices, he will lose the next election. A populist government therefore will try to push for rate cuts before the slowdown becomes evident, hoping to paper over the damage its policies are inflicting.

Of course, in the United States, unlike say Turkey, the president can’t simply order the Fed to cut rates. But Project Syndicate makes an important point: Once the line between monetary and political and monetary policy becomes blurred, and markets realize that rate cuts are not supported by the data, risk premiums will rise, driving up borrowing costs. In the end, it’s the market that decides the rate.

Ray Dalio warns that rising inequality is turning the US into an autocratic state, and he condemned business leaders for failing to stand up to Trump’s policies.

The founder of Bridgewater Associates said, “gaps in wealth” and a collapse in trust were driving “more extreme policies” in the US.

Speaking to the Financial Times, the veteran financier said many western countries were affected by growing inequality, leading voters to turn increasingly to autocratic leaders.

“I think that what is happening now politically and socially is analogous to what happened around the world in the 1930-40 period,” he said.

“Classically, increased wealth and value gaps lead to increased populism of the right and populism of the left and irreconcilable differences between them that can’t be resolved through the democratic process.

“So, democracies weaken, and more autocratic leadership increases as a large percentage of the population wants government leaders to get control of the system to make things work well for them.”

Dalio is alarmed at Trump’s interference in the decisions of the supposedly independent central bank, and the buying of shares in corporations to further his “Made in America” program.

US to take 10% equity stake in Intel, in Trump’s latest corporate move

Dalio said attacks on the Fed “would undermine the confidence in the Fed defending the value of money and make holding dollar-denominated debt assets less attractive which would weaken the monetary order as we know it”.

Conclusion

Trump is highly motivated to get the Fed to cut interest rates so that he doesn’t have to finance the national debt at higher rates when US Treasury bonds roll over. It looks like Trump will get his wish.

He nominated Stephen Miran, chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, to replace Adriana Kugler on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Fed Governor Christopher Waller, viewed as more dovish, could be Trump’s pick to lead the central bank, reinforcing expectations of easier policy. Trump could either fire Powell or wait until his term ends next May before appointing a successor more to his liking.

Gold’s real secular move has yet to even begin – Richard Mills

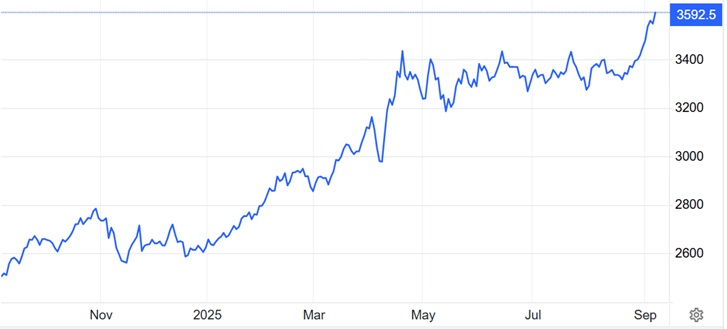

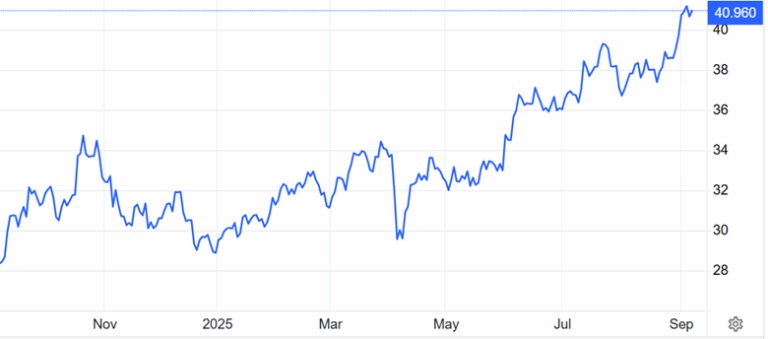

Interest rate cuts are a tailwind for precious metals. Gold is up over a third year to date, hitting $3,500 an ounce for the first time ever this week. Silver had done even better, rising 42%.

One Year Silver Chart, Source Trading Economics

The dollar, meanwhile, suffered its worst first-half performance in 50 years. A low dollar is generally good news for gold and gold stocks.

One year DXY, Source Trading Economics

Barron’s pointed out that gold is getting a tailwind from buying by central banks, and said that gold’s recent rally, and the signals it echoes, shouldn’t be dismissed as merely an inflation warning. It is a signal that the U.S. is at risk of losing its role at the center of the financial system as doubts rise about the dollar’s long-term value.

Some investors are now increasingly betting the president’s assault on the Fed will put the US economy on a darker path, which could lead to a weaker currency and rising price pressures, making gold a more appealing asset. (Bloomberg)

The publication notes that when similar dynamics took hold in the 1970s — with the dollar slumping as then-US President Richard Nixon pressured the Fed to keep rates low in the face of inflation risks — it helped kickstart a 300% rally in gold prices.

Jerry Prior, chief executive officer of $1.7 billion hedge fund Mount Lucas Management LP, said that gold could reach $3,800 an ounce if the Fed rapidly executes three or four cuts by the end of the year.

“The safe-haven assets used to be US dollar assets, but they’re looking less and less of a safe haven now,” said Alexandre Carrier, portfolio manager at DNCA Invest Strategic Resources Funds. “As a default, gold looks like one of the last safe havens.”

Long-time gold bug Peter Schiff notes that foreign governments and central banks now own more gold than US Treasury securities — meaning that foreign governments put more trust in gold than in the US government.

Foreign central banks are selling their dollars to buy gold. Inflation is a big risk for them. While it’s unlikely the US would ever default on its debt, it’s highly likely that Uncle Sam will turn to the printer to solve its debt problems.

And any foreign central bank which owns a ton of US debt doesn’t want to be paid back with inflated dollars. Better to minimize that exposure now and pare down their dollar holdings.

What do they buy instead? Gold.

Let’s check back on our Inflation Mountain Chart, I got the following from Gold Stock Manias posted on 321Gold.com. Note the “Price On” date of 12/29/1978, and than look at Apollo’s inflation mountain chart.

Gold and silver stocks clearly had a massive reaction to the mountain of inflation being unleashed.

Gold Producers’ Stock Performance in ’79/’80

Junior Gold Stock Performance in ’79/’80

Last words go to Ryan McMaken,

“If the Fed pushes for lower rates right now — which requires more money creation from the FOMC’s open market operations — then the Fed will be “loosening into inflation.” That is, the Fed will be adopting looser, more inflationary monetary policy at the same time that there is an upward trend in price inflation.

Not only are CPI and PPI prices accelerating again, but the US is in the midst of a melt up with the S&P 500 near all-time highs, with gold, crypto, and more all ripping to new highs. This is not an economy with too little liquidity. This is an economy with trillions of dollars from the covid-era mega-inflation still sloshing around the economy.

Powell also fears undermining Fed legitimacy by triggering price inflation reminiscent of the 1970s – or even reminiscent of 2022 when CPI inflation hit 40-year highs.” Mises

Richard (Rick) Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

*********